Wie wir ja spätestens seite der Lektüre des Artikels “Galvanische Korrosion auf Booten” wissen, stellt der richtige Schutz vor galvanischer oder elektrolytischer Korrosion eine (lebens-)wichtige Maßnahme für die Sicherheit von Boot und Mannschaft dar.

In the case of the “Random Harvest”, it was only thanks to the experienced and swift actions of the skipper that a sinking could be prevented.

But let’s be honest: in such a stressful situation, how many of us would have thought of converting the engine’s seawater pump into an emergency bilge pump? I invite you, dear reader, to simply go through the more likely alternative scenarios in your mind.

The sacrificing anode

Without a doubt, the best strategy for the average recreational skipper is to use the right (and preventative) means in the fight against electrochemical corrosion.

While owners of steel or aluminum boats often have to deal with relatively complex issues in this respect, this task is fortunately a somewhat more moderate challenge for GRP boats.

One of the most important measures is choosing the right sacrificial anodes. As their name suggests, their task is to sacrifice themselves for the metal parts that are installed on our hull by providing electrons.

And in order for it to do this, it must have a higher residual voltage potential than the nearest base metal that we intend to protect. As a rule of thumb, this potential difference should be at least -200mV.

The metals with the highest residual stress potential, i.e. magnesium and zinc, are therefore often found when we look at the selection of sacrificial anodes in the relevant accessory catalogs.

Sacrificial anodes made of various aluminum alloys are probably somewhat less prominent, although their use also seems to have increased in recent years.

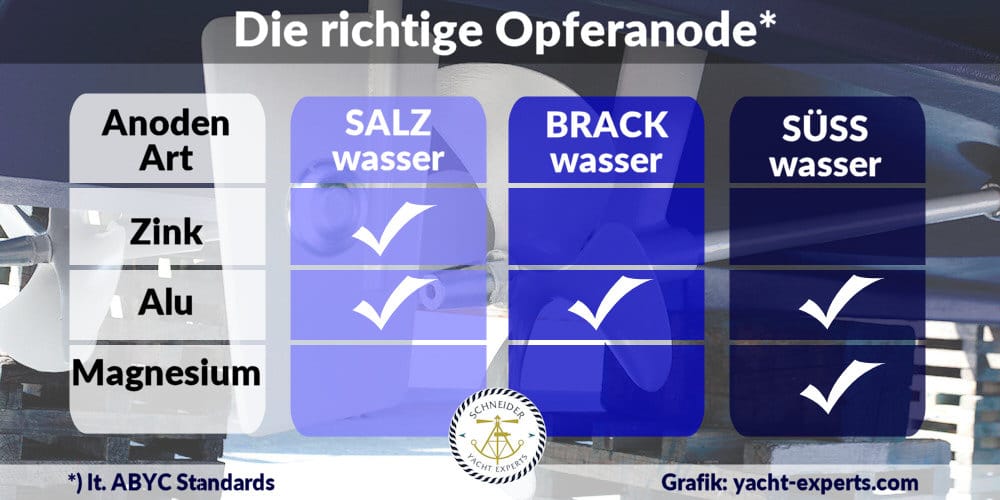

Another important factor in determining the right anode material is the area where our boat will spend most of its time:

The reason for this is that the electrical conductivity of water increases with increasing salt content or contamination, which means that the effectiveness of the anodes also varies.

Against this background, it is also strongly advised not to use magnesium anodes in seawater, as their high intrinsic potential in conjunction with the good conductivity of the salt water can also result in “overprotection”, which can also lead to corrosive damage, especially to aluminum parts (outboard motor/Z-drive).

The electron that comes from afar

So far so good. So now we know what to consider when choosing sacrificial anodes. Time to sit back and move on to more entertaining reading, you might think.

If it weren’t for the famous “just a moment” that the physics teacher used to shout at us when we were too hasty in closing the books. But why? We now have a carefully selected anode that protects all our underwater metals on the boat. Where else could there be a problem? Quite simply: right next to them!

Because as soon as you are moored in a marina, you are usually surrounded by other boats. And even your immediate neighbor’s boat can, under certain circumstances, use insidious electron attacks to ensure that your through-hulls, Z-drives or shafts are attacked. And all this while you are peacefully taking a maneuvering sip together!

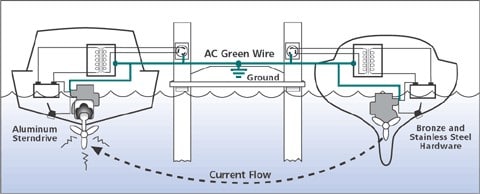

When you came back from your relaxing boat trip, you plugged in the shore power to charge the batteries and have refreshing drinks in the fridge again.

And because your boat’s earthing cable, as well as the earthing cables of all the other boats in the marina, run into one and the same line on the land side, you have effectively joined together to form a huge battery.

And any kind of unwanted fault or leakage currents in their electrical installations can now flow unhindered through your boat and lead to electrolytic corrosion. Or at least accelerate the death of your expensive anodes.

Galvanic insulators and isolating transformers

By now at the latest, we have reached a point where we need to bring out the big guns in the fight against unwanted electron traffic.

And the choice of weapons here clearly falls on galvanic isolators or isolating transformers, which ensure that our own earthing line remains separated from the marina’s or other boats’ earthing, or is only established in the event of a short circuit on board in order to trip circuit breakers properly.

Interested readers should ask their trusted specialist dealer to explain the intricacies of how it works, or research the inexhaustible wisdom of the Internet, especially as the description of this would clearly go beyond the intended purpose of this article.

First of all, it is important to know that they keep extraterritorial electrons away from our own boat and are therefore an essential part of effective corrosion protection as soon as we have a shore power connection.

Equipotential bonding: everything in line, or what?

One last point to consider would be the role of so-called “potential equalization” in our overall protection system. After all, the most expensive sacrificial anode is of little use if it is left to vegetate on its own somewhere on the outside of our hull.

Instead, we must ensure that it can deliver its surplus electrons efficiently to where they are needed.

And as we know, nothing beats a solid cable for this purpose that connects the sacrificial anode(s) to the underwater installations to be protected – preferably without corroded connections or damaged insulation.

Whether all underwater installations should be included or only main components such as the drive, shaft or steering gear is always the subject of controversial discussions.

However, the US ABYC standards (E-11) provide a clear guideline here:

“All electrically conductive … installations that are in contact with bilge or seawater” would therefore have to be connected to the equipotential bonding or the anodes.

I recommend that you obtain information on this from the manufacturer of your boat.

Trust is good, control is better!

So let us summarize:

An effective protection system against electrochemical corrosion includes the following points:

- Material and number of suitable sacrificial anodes

- The installation of galvanic isolators or isolating transformers (for boats with shore power)

- And a properly installed potential equalization (=cable) between anode(s) and UW fittings

You should therefore regularly check that these essential components on your boat are in good working order.

![]() Check the condition of your sacrificial anode(s) at least once a season.

If they are 50% or more depleted, replace them in good time.

Check the condition of your sacrificial anode(s) at least once a season.

If they are 50% or more depleted, replace them in good time.

![]() When purchasing sacrificial anodes, avoid giving preference to the cheapest offer alone. Only high-quality alloys guarantee optimum protection.

The indication of a US Mil specification (according to Navy standards) is an essential quality feature.

When purchasing sacrificial anodes, avoid giving preference to the cheapest offer alone. Only high-quality alloys guarantee optimum protection.

The indication of a US Mil specification (according to Navy standards) is an essential quality feature.

![]() Regularly check the connection between the anode(s) and the UW metals to be protected.

Pay close attention to insulation faults or corroded connections.

The electrical resistance in this potential equalization should not exceed 1 ohm!

Regularly check the connection between the anode(s) and the UW metals to be protected.

Pay close attention to insulation faults or corroded connections.

The electrical resistance in this potential equalization should not exceed 1 ohm!

![]() Check the condition of cabling that runs in the bilge.

Poorly made connections to bilge pumps or float switches are common causes of leakage currents.

Check the condition of cabling that runs in the bilge.

Poorly made connections to bilge pumps or float switches are common causes of leakage currents.

![]() Only use chargers that are designated for marine applications.

A fixed installation of conventional car chargers is not recommended!

Only use chargers that are designated for marine applications.

A fixed installation of conventional car chargers is not recommended!

![]() Always keep an eye on the condition of your on-board outlets, seacocks and other UW installations.

If you notice excessive signs of corrosion, urgent action is required!

Always keep an eye on the condition of your on-board outlets, seacocks and other UW installations.

If you notice excessive signs of corrosion, urgent action is required!

Judge with expertise

But above all, always keep in mind that you are dealing with a topic that actually fills entire libraries.

And this article is merely intended to raise your awareness, but by no means claims to make the reader an expert in marine corrosion.

If in doubt, you should therefore always ask a qualified person to check the cathodic protection or the associated installations.

Licensed electrical installation companies are a good place to start. Although marine electrics have a few pitfalls that are not found in normal domestic installations.

So when choosing a specialist, always ask whether they are familiar with the relevant ISO 10133 and ISO 13297 standards.

These are part of the European “Recreational Craft Directive” and include the relevant regulations for electrical installations on boats. They should therefore be assumed to be known.

It should also be possible to determine the “hull potential” of the boat using a reference electrode in order to check the efficiency of the cathodic protection system with regard to the type and number of anodes and the presence of any leakage currents.

Equipped in this way, you and your boat should be spared the fate of the “Random Harvest”.

With this in mind, I wish you a hearty ahoy and always the famous hand’s breadth of water under your keel.

Yours Ing.

Ingolf Schneider, MASc (AssocRINA)

Expert for boats and yachts